Fascism and Antifascism: Finsbury Park and the 1930s

This blog by Dr Paul Jackson, Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Northampton, provides an introduction to his Heritage Talk which can be seen in full on YouTube.

Clashes between fascists and antifascists are often in the news.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, Donald Trump talked about antifascists being ‘terrorists’, while at the same time behaving favourably to those who seem to support contemporary fascist agendas in America. Clashes between fascists and racists on the one hand, and those who speak out against racism on the other, are not new and episodes in the history of racist politics can help us think about these issues today. This blog reflects on confrontations between fascists and antifascists occurred regularly in 1930s Britain, including in Finsbury Park.

There were a wide range of groups and organisations promoting fascist agendas in interwar Britain. These included the British Fascisti, set up in 1923 by Rosa Lintorn Orman. This groups shows us that the first openly fascist leader in Britain was a woman, and as historians such as Julie Gottlieb point out, the gender history of fascism is often more complex than clichés would first suggest. Other fascist groups also included the Imperial Fascist League, a small but extraordinarily antisemitic group led by Arnold Leese. Contemporary neo-Nazism in Britain can be traced back to the influence of this virulent propagandist for Nazism.

However, the most significant of the fascist groups in Britain was Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF), created in 1932 and reaching a height of perhaps 50,000 members by 1934. From the mid-1930s it developed a closer allegiance to Nazi Germany, changing its name to British Union of Fascists and National Socialists, and by the later 1930s was reinventing itself again as an ostensibly pacifist movement opposed to a new war with Germany. The BUF is often remembered as a failure, yet historians credit it with being able to develop a sustained fascist sub-culture in interwar Britain, one capable of offering activists a genuinely British fascist way of life – even though it was far from any political power.

By the 1930s, antifascists came in many varieties too, from Jewish groups concerned at the rise in antisemitism, to communists who saw fighting fascists as part of fighting for the revolution. There were also liberal and even conservative voices who saw dangers in fascist activism. Leading historian of antifascism, Nigel Copsey, highlights that a fundamental distinction between the fascist and antifascist outlook is their views on democracy. While fascists oppose democracy in any meaningful form, and believe in a world that is inherently unequal, antifascists defend democracy, even if they choose militant tactics to do so. The two are quite different; they are not opposing sides of the same coin.

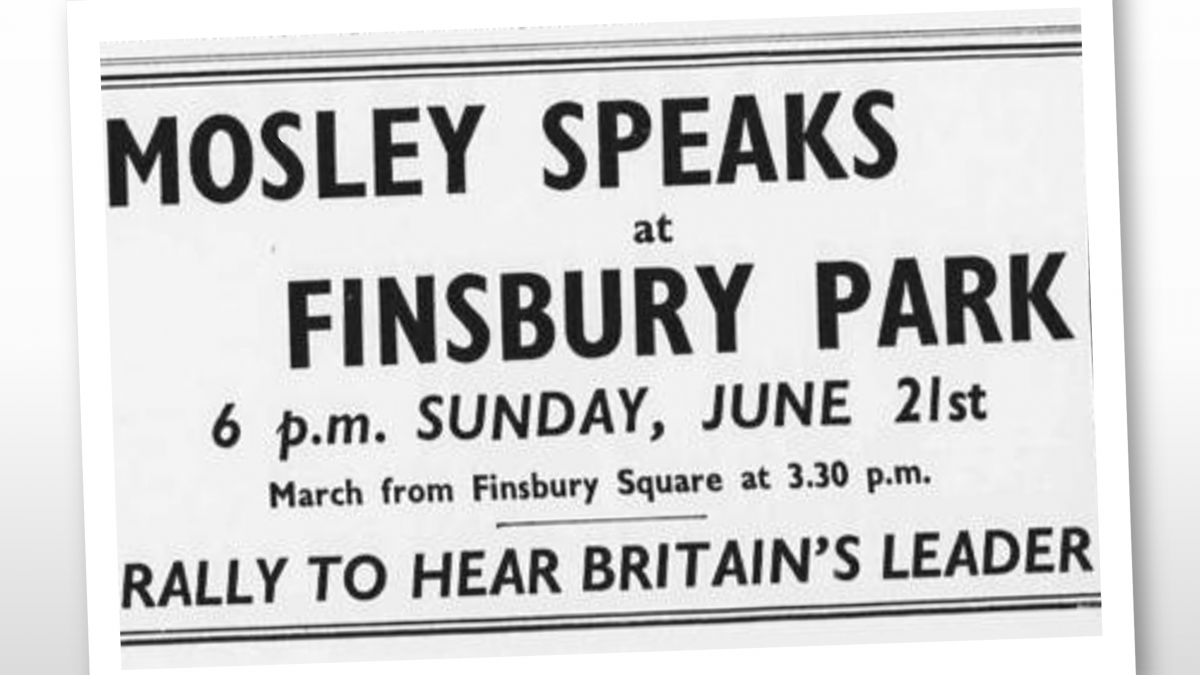

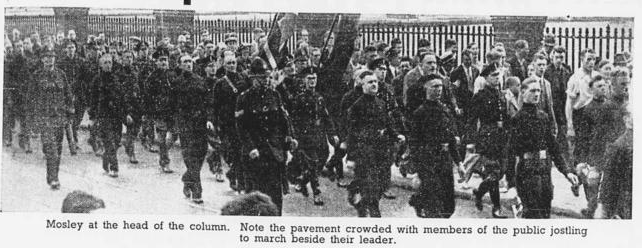

As antifascists confronted the BUF in the 1930s, clashes between the two became a regular feature. This included, on 21 June 1936, at a BUF rally that began at Finsbury Square at 3.30pm and culminated with a speech by Mosley in Finsbury Park at around 6.00 pm. By this time, such events were leading to a significant policing cost, and the rally led to questions in the House of Commons.

Mr Frederick Montague, Labour MP for Islington West, gave a very vivid picture of the nature of such rallies, asking the Home Secretary if he was aware of the:

number of mounted and other police drafted into Finsbury Park yesterday on the occasion of a Fascist demonstration and upon whom falls the cost of these, with police cars, lorries, and ambulance wagons and refreshment tent erected in the children's playground; whether he is aware that the only violence exhibited was that of Sir Oswald Mosley’s supporters; that the demonstration was organised in military fashion with uniformed men and appropriately distinguished officers, that military formations were conducted and military orders given by loud speakers, although loud speakers of a perfectly peaceful rival meeting were ordered to be toned down; and will he take steps to see that, while safeguarding free speech, such extremely provocative private army organisation is forbidden in future?

Here we see a picture of fascism as militaristic and threatening. Why was the state defending the rights of such people to protest in such an overtly paramilitary way, Montague wondered? Surely the law should be changed?

Conveying the reasoning behind the police response, Home Secretary John Simon, replied:

… I am informed by the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis that 573 foot police and 59 mounted police were on the ground. So large a number of police was employed because the police had reason to believe from past experience that the presence of Fascists and anti-Fascists in the park, unless adequately policed, was likely to give rise to disorder and breaches of the peace … The House will appreciate how difficult the task of the police is when rival organisations demonstrate in the same locality. While it is the duty of the police to deal with any conduct which is likely to lead to breaches of the peace, such drastic measures as those proposed by the hon. Member would require legislation, and, as at present advised, I am not satisfied that there is sufficient ground for proposing so far-reaching a change in the law.

The Government response argued the need for policing was the consequence of antifascists, as well as fascists, quite different from the Labour perspective. Simon added in the exchange: ‘The difficulty is that this is a free country, and the best thing we can do is to appeal to everyone on all sides to show a certain amount of reasonableness.’ This raises the awkward but necessary question of whether one could expect a group like the BUF – whose ideology was based on antisemitic conspiracy theories and racism – to be ‘reasonable’?

This was not the only perspective to place blame on antifascists for creating a dynamic where disorder was likely. As a quote from a local news report of the time added, ‘We have no sympathy for the Blackshirts, but it is our opinion that the Fascists’ meeting would have been peaceful if there had been no counter demonstration.’

Interestingly, the ostensibly insurmountable difficulties of changing the law to ban political uniforms and militaristic style of public politics were overcome only a few months later, following what has become known as the Battle of Cable Street. Here, the BUF decided to hold a march though the East End, on 4 October 1936, yet were greeted by thousands of anti-fascist supporters. Police tried to allow BUF marchers to carry out their event, but the size of the antifascist protest was too large, and so eventually the march was called off. This high-profile event has fallen into Britain antifascist mythology as an example of a crucial victory over a fascist movement.

The Battle of Cable Street led to the passing of the Public Order Act of 1936, largely directed at stymieing the BUF. This Act banned uniformed political movements and placed a range of other limitations on the BUF’s style of politics. In 1940, the BUF was closed down by the Government, under Defence Regulation 18b, as it was seen as a security threat, as were other fascist groups.

Should fascist marches be tolerated, as part of protecting the freedom of speech? If so, should antifascists be able to protest too? If they do protest, is it right that they are dismissed as part of the same problem? Can a credible political response to racism be for all sides to ‘be reasonable’?

Perhaps one key lesson to take from the clashes between fascists and antifascists of the 1930s is that tenacity and standing for democracy, and against racism, will yield results, even if you have to endure some criticism from some sections of the press and some politicians.

Paul Jackson is the author of Colin Jordan and Britain’s Neo-Nazi Movement: Hitler’s Echo (Bloomsbury, 2017), and editor of Bloomsbury’s Modern History of Politics and Violence book series.

See the full talk here.